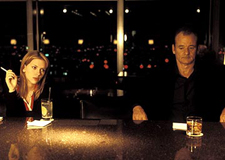

Lost in Translation (Sofia Coppola, 2003)

Sofia Coppola delivers her eagerly

anticipated second feature with Lost in Translation, a well observed but

slight mood piece that follows up her excellent adaptation of The Virgin

Suicides. Without much of a script, and with a slightly improvisational

feel, the Japan-set film observes Bob (Bill Murray), an aging actor who’s in

town while filming a commercial, and Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson), a young

Yale graduate who is accompanying her photographer husband, as they strike up a

relationship to find comfort from their jet-lag fueled malaise. There exists a

thin line between simplicity and subtlety in filmmaking, and to these eyes Lost

in Translation brushes closer to the former than the latter. It is admirable

because it does clearly invest itself in the lead characters’ emotional lives

and it does a good job of showing us what it is that they see when they look at

the world around them, but it doesn’t know what to make of it, so it finally

falls back on trite melodrama, exploding and stretching the moment where they

realize they’ll have to part to an unfortunate extent. Although it’s the

sort of smart, deeply felt American film that I wish were made more often, I

can’t ignore that it’s not as deep as it seems to think it is. For all of

the existential concern that is mustered, a character’s frustrated gripe of

“I don’t know what I’m supposed to be!” is as in-depth as it ever gets.

Attractive and pleasant as it is, there’s no escaping the impression that it

feels like an overly hip exercise in soul-searching for those who thought American

Beauty really did “look closer” at life.

Sofia Coppola delivers her eagerly

anticipated second feature with Lost in Translation, a well observed but

slight mood piece that follows up her excellent adaptation of The Virgin

Suicides. Without much of a script, and with a slightly improvisational

feel, the Japan-set film observes Bob (Bill Murray), an aging actor who’s in

town while filming a commercial, and Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson), a young

Yale graduate who is accompanying her photographer husband, as they strike up a

relationship to find comfort from their jet-lag fueled malaise. There exists a

thin line between simplicity and subtlety in filmmaking, and to these eyes Lost

in Translation brushes closer to the former than the latter. It is admirable

because it does clearly invest itself in the lead characters’ emotional lives

and it does a good job of showing us what it is that they see when they look at

the world around them, but it doesn’t know what to make of it, so it finally

falls back on trite melodrama, exploding and stretching the moment where they

realize they’ll have to part to an unfortunate extent. Although it’s the

sort of smart, deeply felt American film that I wish were made more often, I

can’t ignore that it’s not as deep as it seems to think it is. For all of

the existential concern that is mustered, a character’s frustrated gripe of

“I don’t know what I’m supposed to be!” is as in-depth as it ever gets.

Attractive and pleasant as it is, there’s no escaping the impression that it

feels like an overly hip exercise in soul-searching for those who thought American

Beauty really did “look closer” at life.

Most of the grief that Bob feels during

his sojourn in Japan is expressed through his frustration and bemusement at the

Engrish he hears the natives speaking. Though watching Japanese people stumble

over phrases like “rip my stockings” and “Rat Pack” might sound

uncomfortably close to racism, I don’t think the film itself is offensive

because the scenes in question are really only showing us Bob’s jaundiced

point of view. It’s this same point of view that makes him feel the idea of

making small talk in a bar is utterly ridiculous and it’s the presentation of

this same point of view that explains why the camera looks at a female movie

star and a lounge singer with disdain. While it may be questionable whether or

not an approximation of Bob’s state of mind is worth having to sit through a

seemingly unlimited series of scenes in which everyone who’s not Bob or

Charlotte feels like a loser, it’s tough to be offended by the mere

presentation of this character’s (and not the movie’s) worldview. When he

finally starts spending time with Charlotte, Bob fills the uncomfortable

silences between them by laughing at language quirks with her. It serves as

common ground for them because it passive aggressively expresses their unspoken

disdain for an environment that they perceive as hostile.

Most of the grief that Bob feels during

his sojourn in Japan is expressed through his frustration and bemusement at the

Engrish he hears the natives speaking. Though watching Japanese people stumble

over phrases like “rip my stockings” and “Rat Pack” might sound

uncomfortably close to racism, I don’t think the film itself is offensive

because the scenes in question are really only showing us Bob’s jaundiced

point of view. It’s this same point of view that makes him feel the idea of

making small talk in a bar is utterly ridiculous and it’s the presentation of

this same point of view that explains why the camera looks at a female movie

star and a lounge singer with disdain. While it may be questionable whether or

not an approximation of Bob’s state of mind is worth having to sit through a

seemingly unlimited series of scenes in which everyone who’s not Bob or

Charlotte feels like a loser, it’s tough to be offended by the mere

presentation of this character’s (and not the movie’s) worldview. When he

finally starts spending time with Charlotte, Bob fills the uncomfortable

silences between them by laughing at language quirks with her. It serves as

common ground for them because it passive aggressively expresses their unspoken

disdain for an environment that they perceive as hostile.

Coppola’s other attempts to articulate

this feeling aren’t as successful, however. During one scene, when Charlotte

places a long-distance call to a friend, she gets put on hold, and if it

weren’t such a nice acting moment it would be an unbearably strained metaphor

for her feelings of loneliness. Unfortunately, the same scenario is later

repeated when a cell phone cuts out in a scene that’s much more glib. In a

similarly clumsy manner, her husband (Giovanni Ribisi) repeatedly says “love

you” to her and demonstrates his general inattention by not really listening

to her when she speaks. Worse still, the first half hour of the film, which

mostly follows Bill, feels like an extended version of About Schmidt’s

awful waterbed scenes in the ways it combines the disdain he feels toward

people’s regional quirks with the hell that he faces in the hotel’s

gadgetry. Thankfully, the scenes that detail Charlotte’s point of view

dominate the second half hour and then when the two finally begin talking, the

movie suitably adopts a third tone. It’s interesting, but one wonders if all

of this is enough to sustain interest in a feature film. The movie’s prime

revelation seems to be that if you spend time in a foreign country all alone

you’ll be lonely, and as such it’s an experiential movie that doesn’t

aspire to show us something that we haven’t previously experienced. The main

characters seem interesting primarily because the camera focuses its attention

on them, though that kind of plainness might be a virtue. Nonetheless, the

script seems caught in between being smart enough to realize that the main

characters aren’t exactly profound and being too dumb to make a profound

statement about what they lack. As much as it calls them on their plainness, it

still invests itself fully in their point of view, as if it had nothing more to

say about them than what the characters themselves realize about themselves.

Coppola’s other attempts to articulate

this feeling aren’t as successful, however. During one scene, when Charlotte

places a long-distance call to a friend, she gets put on hold, and if it

weren’t such a nice acting moment it would be an unbearably strained metaphor

for her feelings of loneliness. Unfortunately, the same scenario is later

repeated when a cell phone cuts out in a scene that’s much more glib. In a

similarly clumsy manner, her husband (Giovanni Ribisi) repeatedly says “love

you” to her and demonstrates his general inattention by not really listening

to her when she speaks. Worse still, the first half hour of the film, which

mostly follows Bill, feels like an extended version of About Schmidt’s

awful waterbed scenes in the ways it combines the disdain he feels toward

people’s regional quirks with the hell that he faces in the hotel’s

gadgetry. Thankfully, the scenes that detail Charlotte’s point of view

dominate the second half hour and then when the two finally begin talking, the

movie suitably adopts a third tone. It’s interesting, but one wonders if all

of this is enough to sustain interest in a feature film. The movie’s prime

revelation seems to be that if you spend time in a foreign country all alone

you’ll be lonely, and as such it’s an experiential movie that doesn’t

aspire to show us something that we haven’t previously experienced. The main

characters seem interesting primarily because the camera focuses its attention

on them, though that kind of plainness might be a virtue. Nonetheless, the

script seems caught in between being smart enough to realize that the main

characters aren’t exactly profound and being too dumb to make a profound

statement about what they lack. As much as it calls them on their plainness, it

still invests itself fully in their point of view, as if it had nothing more to

say about them than what the characters themselves realize about themselves.

It’s unfortunate that I found

Murray’s performance in Lost in Translation problematic, because

embracing the film seems completely dependent on enjoying it. He plays a

character who remains above it all in his own mind, and we’re supposed to be

touched when Charlotte finally breaks through his glibly ironic exterior.

Murray’s typical comedic persona often depends on this unlikable, self-imposed

isolation from the rest of the film that he appears in (e.g. Charlie’s

Angels), so it’s unfortunate to see him in a film that accepts that

persona unquestionably, even if it does eventually try to break it down with

warm fuzzies. His work in Rushmore seemed to probe that comic

resignation. Here it’s a given. When he tries to stretch for a big scene, such

as in the one in which he gives a karaoke rendition of “More Than This”, he

doesn’t really inhabit the character. Johansson fares a bit better.

In that same karaoke scene, her rendition of “Brass in Pocket” is

made all the more affecting by the tiny squeaks in her voice. She’s not quite

convincing, however, as a student who recently graduated from Yale Philosophy

(perhaps because the movie attempts

to show her process of questioning by doing shallow stuff like listening to

self-help CDs and attempting to connect with Japanese culture by arranging

flowers and visiting temples).

It’s unfortunate that I found

Murray’s performance in Lost in Translation problematic, because

embracing the film seems completely dependent on enjoying it. He plays a

character who remains above it all in his own mind, and we’re supposed to be

touched when Charlotte finally breaks through his glibly ironic exterior.

Murray’s typical comedic persona often depends on this unlikable, self-imposed

isolation from the rest of the film that he appears in (e.g. Charlie’s

Angels), so it’s unfortunate to see him in a film that accepts that

persona unquestionably, even if it does eventually try to break it down with

warm fuzzies. His work in Rushmore seemed to probe that comic

resignation. Here it’s a given. When he tries to stretch for a big scene, such

as in the one in which he gives a karaoke rendition of “More Than This”, he

doesn’t really inhabit the character. Johansson fares a bit better.

In that same karaoke scene, her rendition of “Brass in Pocket” is

made all the more affecting by the tiny squeaks in her voice. She’s not quite

convincing, however, as a student who recently graduated from Yale Philosophy

(perhaps because the movie attempts

to show her process of questioning by doing shallow stuff like listening to

self-help CDs and attempting to connect with Japanese culture by arranging

flowers and visiting temples).

The supporting cast is a mixed bag,

since the extreme reliance on the points of view of the two leads cripples the

audience’s opportunity to get a good look at them. A famous Hollywood actress

played by Anna Faris has the most noticeable pulse of the cast members, but is

given precious little to do and deemed worthy of our scorn mostly because

she’s not one of the two leads. Faris still demonstrates a fair amount of

comic wit in what’s essentially a caricature, and it’s unfortunate her

character isn’t better developed. At one point, it seems to be implied through

body language that Charlotte’s husband, played by Ribisi, has slept with her,

but because of the intense focus on the two central characters, we don’t get a

solid read on the situation. Ribisi establishes that his character is a workaholic,

suggests that he might not be sophisticated enough for his wife’s tastes, and

then basically disappears from the screen. Bob’s wife is never shown on

screen, and we only overhear her phone calls to him, but the spiteful delivery

of her dialogue is effective (if a bit arch) in making us understand why he

doesn’t want to return home. Every one of her line readings sounds like an

accusation. The only moment in their conversations that feels forced occurs when

she hangs up as he finally says, “I love you.” The rest of the characters,

perhaps necessarily, float into and out of Charlotte and Bob’s lives without

making much impact.

The supporting cast is a mixed bag,

since the extreme reliance on the points of view of the two leads cripples the

audience’s opportunity to get a good look at them. A famous Hollywood actress

played by Anna Faris has the most noticeable pulse of the cast members, but is

given precious little to do and deemed worthy of our scorn mostly because

she’s not one of the two leads. Faris still demonstrates a fair amount of

comic wit in what’s essentially a caricature, and it’s unfortunate her

character isn’t better developed. At one point, it seems to be implied through

body language that Charlotte’s husband, played by Ribisi, has slept with her,

but because of the intense focus on the two central characters, we don’t get a

solid read on the situation. Ribisi establishes that his character is a workaholic,

suggests that he might not be sophisticated enough for his wife’s tastes, and

then basically disappears from the screen. Bob’s wife is never shown on

screen, and we only overhear her phone calls to him, but the spiteful delivery

of her dialogue is effective (if a bit arch) in making us understand why he

doesn’t want to return home. Every one of her line readings sounds like an

accusation. The only moment in their conversations that feels forced occurs when

she hangs up as he finally says, “I love you.” The rest of the characters,

perhaps necessarily, float into and out of Charlotte and Bob’s lives without

making much impact.

There are lovely moments of tenderness

throughout Lost in Translation that should make the film something to

treasure, but they aren’t enough. The final private moment in a crowded space

is thankfully left private, but it loses some impact because of the niggling

feeling that the awkward adieu that came before would have made for a better

ending. The film recalls Hiroshima, Mon Amour and Friday Night,

but focuses more intently on friendship than romantic entanglement. It becomes

apparent that Charlotte and Bob share the realization that those closest to them

just want affirmations of what they say when they talk, and they bond because

they want an affirmation of that fact from each other.

There are lovely moments of tenderness

throughout Lost in Translation that should make the film something to

treasure, but they aren’t enough. The final private moment in a crowded space

is thankfully left private, but it loses some impact because of the niggling

feeling that the awkward adieu that came before would have made for a better

ending. The film recalls Hiroshima, Mon Amour and Friday Night,

but focuses more intently on friendship than romantic entanglement. It becomes

apparent that Charlotte and Bob share the realization that those closest to them

just want affirmations of what they say when they talk, and they bond because

they want an affirmation of that fact from each other.

These moments of revelation are few and

far between, however, and Lost in Translation only shakes its sense of

fashionable dislocation and becomes truly successful for about a stretch of film

that takes place during their first date. The Chemical Brothers and Squarepusher

are used well on the soundtrack during this extended nightclub and after-party

sequence that lasts about fifteen minutes and actually works to the degree that

you wish the rest of the film did. There even is a random run through the

streets of Tokyo that seems to be placed there so the unadventurous members of

the audience can experience the pop excitement of a Wong Kar-Wai film. During

that karaoke scene, there’s the realization that pop songs they sing and hear

seem to say what the characters want to, but if that was all the characters

wanted to say to each other, they’d be able to say it, and the moment

wouldn’t feel so sublime. Throughout this section of the film, which

approaches magnificence in its own small way, the precious moments between

Charlotte and Bob seem to be dissolving as they happen and there’s a real

mixture of transient discovery and loss. Unfortunately, this feeling doesn’t

really permeate throughout the film that surrounds these scenes. Lost in

Translation is by no means a bad film, but it frustrates because of its

inability to be better at doing what it’s trying to do. I

might be underrating it, but it feels almost appropriate that my response to a

movie so predicated on conveying a subjective feeling of mood feels moody and

subjective itself.

These moments of revelation are few and

far between, however, and Lost in Translation only shakes its sense of

fashionable dislocation and becomes truly successful for about a stretch of film

that takes place during their first date. The Chemical Brothers and Squarepusher

are used well on the soundtrack during this extended nightclub and after-party

sequence that lasts about fifteen minutes and actually works to the degree that

you wish the rest of the film did. There even is a random run through the

streets of Tokyo that seems to be placed there so the unadventurous members of

the audience can experience the pop excitement of a Wong Kar-Wai film. During

that karaoke scene, there’s the realization that pop songs they sing and hear

seem to say what the characters want to, but if that was all the characters

wanted to say to each other, they’d be able to say it, and the moment

wouldn’t feel so sublime. Throughout this section of the film, which

approaches magnificence in its own small way, the precious moments between

Charlotte and Bob seem to be dissolving as they happen and there’s a real

mixture of transient discovery and loss. Unfortunately, this feeling doesn’t

really permeate throughout the film that surrounds these scenes. Lost in

Translation is by no means a bad film, but it frustrates because of its

inability to be better at doing what it’s trying to do. I

might be underrating it, but it feels almost appropriate that my response to a

movie so predicated on conveying a subjective feeling of mood feels moody and

subjective itself.

48

09-02-03

Jeremy Heilman