|

Newest Reviews:

New Movies -

The Tunnel

V/H/S

The Tall Man

Mama Africa

Detention

Brake

Ted

Tomboy

Brownian Movement

Last Ride

[Rec]≥: Genesis

Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai

Indie Game: The Movie

Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter

Old Movies -

Touki Bouki: The Journey of the Hyena

Drums Along the Mohawk

The Chase

The Heiress

Show

People

The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry

Pitfall

Driftwood

Miracle Mile

The Great Flamarion

Dark Habits

Archives -

Recap: 2000,

2001, 2002,

2003, 2004

, 2005, 2006,

2007 , 2008

, 2009 ,

2010 , 2011 ,

2012

All reviews alphabetically

All reviews by star rating

All reviews by release year

Masterpieces

Screening Log

Links

FAQ

E-mail me

HOME

| |

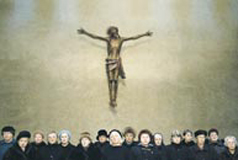

Jesus, You Know (Ulrich Seidl, 2003)

Austrian filmmaker Ulrich Seidlís

documentary Jesus, You Know uses the filmed prayers of a half-dozen

churchgoers to present an unusual, yet insightful, look at the role that

religion plays in modern lives. Thanks to the approach used by Seidl in filming

his subjects, the mundane, or at least familiar, problems that these people

speak of become an informative, riveting and entertaining presentation of a

collective pathos. For a documentary, the film is unusually formally controlled.

As a result, one canít help but suspect that Seidl had his subjects stage

their actions so that the symmetry of his compositions was not upset. He

frequently photographs parishioners from head on, and when they pray, they speak

directly into the camera, addressing the audience as if they were the recipients

of the uttered prayers. The effect that this technique has is almost unsettling

at first, as if Seidl is not only exhibiting their religious being, but also

confronting us with it and forcing us to think of them primarily as spiritual

entities. When his subjects begin speaking, and weíre suddenly made privy to

their innermost passions and plights, this level of discomfort only rises

higher. Austrian filmmaker Ulrich Seidlís

documentary Jesus, You Know uses the filmed prayers of a half-dozen

churchgoers to present an unusual, yet insightful, look at the role that

religion plays in modern lives. Thanks to the approach used by Seidl in filming

his subjects, the mundane, or at least familiar, problems that these people

speak of become an informative, riveting and entertaining presentation of a

collective pathos. For a documentary, the film is unusually formally controlled.

As a result, one canít help but suspect that Seidl had his subjects stage

their actions so that the symmetry of his compositions was not upset. He

frequently photographs parishioners from head on, and when they pray, they speak

directly into the camera, addressing the audience as if they were the recipients

of the uttered prayers. The effect that this technique has is almost unsettling

at first, as if Seidl is not only exhibiting their religious being, but also

confronting us with it and forcing us to think of them primarily as spiritual

entities. When his subjects begin speaking, and weíre suddenly made privy to

their innermost passions and plights, this level of discomfort only rises

higher.

A few times during he movie Seidl cuts

away from those praying, and shows the icon of Christ that the person is

directing their speech at. Alternatively, these representations seem stern,

compassionate and, in one case, almost mocking. It becomes apparent through

Seidlís editing that these icons are blank slates that allow the person in

prayer to project whatever meaning they need to onto them. Similarly, there

seems to be a consistent feeling that the problems of at least some of these

people are mostly self-inflicted. A troubled teenager complains that his family

harasses him for attending church services in lieu of more productive

activities. When he goes on to confess a compulsive tendency to turn television

and even Bible stories into erotic fantasies, it seems that his voluntary

involvement in the church is the sole reason for his guilt. Though we donít

ever see his family, itís not very likely that they are the source of the

pressures that he feels. Similarly, the other people we hear speaking seem to

have their lifeís problems exacerbated by their involvement in the church.

Even though each of them obviously draws strength from their prayers, their

involvement in the church doesnít come without its own costs. When the actual

content of his subjectsí prayers forms not only semi-melodramatic

mini-narratives, but also a thematically consistent vibe of romantic

frustration, it grows even more difficult not to question the veracity of the

entire enterprise. Ultimately, though, it doesnít much matter if the people we

see are expressing their own sentiments or scripted ones. Seidlís attitudes

toward these people are whatís important here, and they are obvious. A few times during he movie Seidl cuts

away from those praying, and shows the icon of Christ that the person is

directing their speech at. Alternatively, these representations seem stern,

compassionate and, in one case, almost mocking. It becomes apparent through

Seidlís editing that these icons are blank slates that allow the person in

prayer to project whatever meaning they need to onto them. Similarly, there

seems to be a consistent feeling that the problems of at least some of these

people are mostly self-inflicted. A troubled teenager complains that his family

harasses him for attending church services in lieu of more productive

activities. When he goes on to confess a compulsive tendency to turn television

and even Bible stories into erotic fantasies, it seems that his voluntary

involvement in the church is the sole reason for his guilt. Though we donít

ever see his family, itís not very likely that they are the source of the

pressures that he feels. Similarly, the other people we hear speaking seem to

have their lifeís problems exacerbated by their involvement in the church.

Even though each of them obviously draws strength from their prayers, their

involvement in the church doesnít come without its own costs. When the actual

content of his subjectsí prayers forms not only semi-melodramatic

mini-narratives, but also a thematically consistent vibe of romantic

frustration, it grows even more difficult not to question the veracity of the

entire enterprise. Ultimately, though, it doesnít much matter if the people we

see are expressing their own sentiments or scripted ones. Seidlís attitudes

toward these people are whatís important here, and they are obvious.

52

12-13-03

Jeremy Heilman

|