Ten Minutes Older: The Trumpet (Aki Kaurismaki, Victor

Erice, Werner Herzog, Jim Jarmusch, Wim Wenders, Spike Lee, & Chen Kaige,

2002)

The portmanteau film is one of the less

impressive genres in cinema, but Ten

Minutes Older: The Trumpet, unlike its companion film The

Cello (really only noteworthy for Godardís entry), is a respectable

collection of shorts. With an impressive list of participating directors

involved, the films all are use time as a theme and run ten minutes long each.

Obviously, some of them are better than others, but none of them are

excruciating, which makes the prospect of digging for the riches within The

Trumpet less daunting than usual. A film-by-film breakdown follows:

The portmanteau film is one of the less

impressive genres in cinema, but Ten

Minutes Older: The Trumpet, unlike its companion film The

Cello (really only noteworthy for Godardís entry), is a respectable

collection of shorts. With an impressive list of participating directors

involved, the films all are use time as a theme and run ten minutes long each.

Obviously, some of them are better than others, but none of them are

excruciating, which makes the prospect of digging for the riches within The

Trumpet less daunting than usual. A film-by-film breakdown follows:

Aki Kaurismškiís entry, Dogs

Have No Hell [36], which features the two leads from his most recent film,

seems on the surface on par with his usual output, but it doesn't work precisely

because of its abbreviated duration. In this pulpy comic drama, Markku Peltola

plays a man who gets out of prison and has ten minutes to get money, get his

girl, get married and catch a train to Moscow. Because the ten minute time limit

forces him to speed up his pace, Kaurismški has to abandon his usual plodding

drollery. The retro rock and roll number is now pressed up more tightly against

the symphonic overtures, and the character quirks that usually inspire laughter

don't have time to register because the clock is always ticking.

Aki Kaurismškiís entry, Dogs

Have No Hell [36], which features the two leads from his most recent film,

seems on the surface on par with his usual output, but it doesn't work precisely

because of its abbreviated duration. In this pulpy comic drama, Markku Peltola

plays a man who gets out of prison and has ten minutes to get money, get his

girl, get married and catch a train to Moscow. Because the ten minute time limit

forces him to speed up his pace, Kaurismški has to abandon his usual plodding

drollery. The retro rock and roll number is now pressed up more tightly against

the symphonic overtures, and the character quirks that usually inspire laughter

don't have time to register because the clock is always ticking.

Victor Ericeís Lifeline

[57] is a refined, subdued and gorgeous black and white study in cinematography.

Though it's from the outset, the story of an injured baby (and the loss of

innocence), it spends several minutes establishing mood before becoming too

overtly symbolic. It captures the feel for life in a Spanish small town, or at

least an idealized black-and-white dream of that feel, and then punctures that

feeling with a slowly building rhythm of portentous symbols (e.g. a snake

crawling amongst apples, a black cat). It's a beautiful experience, but a

simplistic one that only gains any emotional power with the associations that

its final shot inspire. At least one can say that it works better as a short

than it would as a feature.

Victor Ericeís Lifeline

[57] is a refined, subdued and gorgeous black and white study in cinematography.

Though it's from the outset, the story of an injured baby (and the loss of

innocence), it spends several minutes establishing mood before becoming too

overtly symbolic. It captures the feel for life in a Spanish small town, or at

least an idealized black-and-white dream of that feel, and then punctures that

feeling with a slowly building rhythm of portentous symbols (e.g. a snake

crawling amongst apples, a black cat). It's a beautiful experience, but a

simplistic one that only gains any emotional power with the associations that

its final shot inspire. At least one can say that it works better as a short

than it would as a feature.

The third short, Werner Herzogís Ten Thousand Years Older [69], is a fascinating mini-documentary

which examines the discovery of what might perhaps be the last lost tribe. Set

in the Amazon, the film epitomizes Herzogís willingness to go to the ends of

the earth to demonstrate his attitudes about civilizationís debilitating

effects on nature. Genuine tension arises in scenes such as the one showing the

tribeís first contact with modern man, in which a native threatens to spy the

hidden camera recording the event. When Herzog tells us that these few minutes

of contact with the modern world led to the tribeís demise, the film suddenly

shifts into a sadder, but no less interesting mode. Time jumps forward twenty

years, and the effects of the modern world are made apparent. Even if it's not

one Herzogís best works, it's undeniably an excellent piece of moviemaking.

The third short, Werner Herzogís Ten Thousand Years Older [69], is a fascinating mini-documentary

which examines the discovery of what might perhaps be the last lost tribe. Set

in the Amazon, the film epitomizes Herzogís willingness to go to the ends of

the earth to demonstrate his attitudes about civilizationís debilitating

effects on nature. Genuine tension arises in scenes such as the one showing the

tribeís first contact with modern man, in which a native threatens to spy the

hidden camera recording the event. When Herzog tells us that these few minutes

of contact with the modern world led to the tribeís demise, the film suddenly

shifts into a sadder, but no less interesting mode. Time jumps forward twenty

years, and the effects of the modern world are made apparent. Even if it's not

one Herzogís best works, it's undeniably an excellent piece of moviemaking.

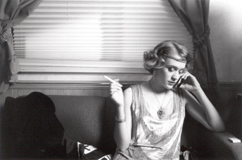

Jim Jarmuschís Int.Trailer.Night

[76], however, just might be one of its makerís finest achievements.

Taking place in real time, and starring Chloe Sevingy, the short goes a long way

toward deglamorizing the myth of the celebrity trailer. Very little of import

happens, beyond the visits a series of technicians make and a cell phone call

that the actress places, but it manages to create a credible portrait of the

actressí role in a production. At once a tool of the film and a personality

who must be catered to above the needs of the film, she exists in a rarefied,

but lonely, zone. The use of real time drives home the tedium inherent in a

filmís shooting schedule. The respect and personal space that sheís given

lead to loneliness, even as sheís being physically violated by a hair stylist

and a sound man. Itís not a deep movie, by any means, but itís perfectly

pitched and surprisingly succinct in the way it goes about making its

observations.

Jim Jarmuschís Int.Trailer.Night

[76], however, just might be one of its makerís finest achievements.

Taking place in real time, and starring Chloe Sevingy, the short goes a long way

toward deglamorizing the myth of the celebrity trailer. Very little of import

happens, beyond the visits a series of technicians make and a cell phone call

that the actress places, but it manages to create a credible portrait of the

actressí role in a production. At once a tool of the film and a personality

who must be catered to above the needs of the film, she exists in a rarefied,

but lonely, zone. The use of real time drives home the tedium inherent in a

filmís shooting schedule. The respect and personal space that sheís given

lead to loneliness, even as sheís being physically violated by a hair stylist

and a sound man. Itís not a deep movie, by any means, but itís perfectly

pitched and surprisingly succinct in the way it goes about making its

observations.

Twelve Miles to Trona [40], by Wim Wenders, is probably the least ambitious

of the shorts. In it, a desperate man (Charles Esten) speeds to a clinic to seek

treatment for an overdose of drugs. Trick lenses distort the American landscape

as the man drives, resulting in a spectacular and surreal display of

pyrotechnics, underscored by music from the Eels. Itís technically adept and

capable of holding oneís attention, but awfully vapid. One canít help but

feel that its attempts to make a larger statement about the American experience

are in vain.

Twelve Miles to Trona [40], by Wim Wenders, is probably the least ambitious

of the shorts. In it, a desperate man (Charles Esten) speeds to a clinic to seek

treatment for an overdose of drugs. Trick lenses distort the American landscape

as the man drives, resulting in a spectacular and surreal display of

pyrotechnics, underscored by music from the Eels. Itís technically adept and

capable of holding oneís attention, but awfully vapid. One canít help but

feel that its attempts to make a larger statement about the American experience

are in vain.

Spike Leeís politically charged We Wuz Robbed [43] rapidly examines the Democratic reaction to the

controversial 2000 Presidential election. Edited with amazing precision, itís

a piece of propaganda that inspires admiration regardless of your political

stance. Leeís examination of those who interceded with Goreís concession to

Bush makes the action seem unabashedly heroic, and, as the title suggests,

thereís no gray area in this movie about what should have been the

electionís proper outcome. It results in a movie thatís an electrifying

experience while viewing it, but also one thatís in no way convincing.

Spike Leeís politically charged We Wuz Robbed [43] rapidly examines the Democratic reaction to the

controversial 2000 Presidential election. Edited with amazing precision, itís

a piece of propaganda that inspires admiration regardless of your political

stance. Leeís examination of those who interceded with Goreís concession to

Bush makes the action seem unabashedly heroic, and, as the title suggests,

thereís no gray area in this movie about what should have been the

electionís proper outcome. It results in a movie thatís an electrifying

experience while viewing it, but also one thatís in no way convincing.

Finally, Chen Kaigeís limply conceived

100 Flowers Hidden Deep [30], is an insubstantial piece of whimsy

that seems odder by its inclusion alongside more serious fare. In it, a

delusional old man hires movers and leads them into a dilapidated old section of

Beijing. When they arrive, they find that there is no home to be moved, but they

humor him in an effort to receive payment. Ostensibly a piece about the loss of

things past, it comes off as mawkish.

Finally, Chen Kaigeís limply conceived

100 Flowers Hidden Deep [30], is an insubstantial piece of whimsy

that seems odder by its inclusion alongside more serious fare. In it, a

delusional old man hires movers and leads them into a dilapidated old section of

Beijing. When they arrive, they find that there is no home to be moved, but they

humor him in an effort to receive payment. Ostensibly a piece about the loss of

things past, it comes off as mawkish.

52

Jeremy Heilman

05-25-04