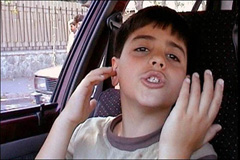

Ten (Abbas Kiarostami) 2002

Ten,

Abbas Kiarostamiís new movie, only puts forth the appearance of

effortlessness. Essentially using just static two camera setups the digitally

filmed motion picture, which is entirely car bound, alternates between showing a

female driver and various passengers as they converse with each other and

enlighten us about womenís rights in Iran. Credit must go to the director for

never turning the talky movie into a shot / reverse shot tennis match as the

actors prattle on. Thereís not a cut at all for the first twenty minutes or so

of action as the director intently focuses on one participant in an argument

between a mother and son. They discuss the recent marriage of the mother to a

man other than the boyís father, who she divorced. Through the surprisingly

naturalistic conversation, the audience comes to learn a bit about the

complexities of Iranian gender politics, but Kiarostami surprisingly doesnít

attempt to turn his female protagonist into some kind of martyr for womenís

rights. Itís revealed that she lied, telling the judge that her husband was a

drug addict, to gain her divorce, and sheís completely unrepentant about it.

If her actions arenít wholly sympathetic, theyíre certainly understandable

given the situation. That the audience understands her plight after spending

only a few moments with her is a testament to the concise nature of this

seemingly random amalgamation of scenes.

Ten,

Abbas Kiarostamiís new movie, only puts forth the appearance of

effortlessness. Essentially using just static two camera setups the digitally

filmed motion picture, which is entirely car bound, alternates between showing a

female driver and various passengers as they converse with each other and

enlighten us about womenís rights in Iran. Credit must go to the director for

never turning the talky movie into a shot / reverse shot tennis match as the

actors prattle on. Thereís not a cut at all for the first twenty minutes or so

of action as the director intently focuses on one participant in an argument

between a mother and son. They discuss the recent marriage of the mother to a

man other than the boyís father, who she divorced. Through the surprisingly

naturalistic conversation, the audience comes to learn a bit about the

complexities of Iranian gender politics, but Kiarostami surprisingly doesnít

attempt to turn his female protagonist into some kind of martyr for womenís

rights. Itís revealed that she lied, telling the judge that her husband was a

drug addict, to gain her divorce, and sheís completely unrepentant about it.

If her actions arenít wholly sympathetic, theyíre certainly understandable

given the situation. That the audience understands her plight after spending

only a few moments with her is a testament to the concise nature of this

seemingly random amalgamation of scenes.

The greatest disappointments in Ten donít come

from Kiarostamiís inability to really open up the drama and make it feel more

universal than it does. Since the intimate focus achieved early on is remains

relatively immediate and lively for the duration of the picture, one should

scarcely care that the movie isnít bigger in scope (indeed, a casual remark

from the protagonist about womenís physical self-image issues feels unwelcome

precisely because it feels so calculated to appeal to Western audiences). What

does hurt the experimentís success, however, is the directorís lack of

explicit justification for setting all of his action in a car. Other Kiarostami

films, which tend to be car bound as well, have done a better job of showing us

why it is that they take place in automobiles. Plenty of ideas pop into my head

on this point. Is it so we can see that the liberated, divorced protagonist is

always in the driverís seat? Is it so we can understand that her journey is

never complete? Is it to show the existence of an intensely private space in the

public thatís both suitable for intimate revelations and public debate? Is it

so the director can take the audienceís focus off of setting (which is

ever-changing here) and place it wholly on character? All of these theses seem

valid to a degree, but none of them seem wholly satisfactory.

The greatest disappointments in Ten donít come

from Kiarostamiís inability to really open up the drama and make it feel more

universal than it does. Since the intimate focus achieved early on is remains

relatively immediate and lively for the duration of the picture, one should

scarcely care that the movie isnít bigger in scope (indeed, a casual remark

from the protagonist about womenís physical self-image issues feels unwelcome

precisely because it feels so calculated to appeal to Western audiences). What

does hurt the experimentís success, however, is the directorís lack of

explicit justification for setting all of his action in a car. Other Kiarostami

films, which tend to be car bound as well, have done a better job of showing us

why it is that they take place in automobiles. Plenty of ideas pop into my head

on this point. Is it so we can see that the liberated, divorced protagonist is

always in the driverís seat? Is it so we can understand that her journey is

never complete? Is it to show the existence of an intensely private space in the

public thatís both suitable for intimate revelations and public debate? Is it

so the director can take the audienceís focus off of setting (which is

ever-changing here) and place it wholly on character? All of these theses seem

valid to a degree, but none of them seem wholly satisfactory.

The achievements of Ten are considerable enough to

outweigh even such a major quibble as that, however. Kiarostamiís use of

off-screen space to enhance the world his films take place in is as adroit as

ever here. Although this movie sometimes seems randomly put together, thereís a fair

amount of craft on display. Kiarostami uses jump cuts to compress what still

feels like real time. He also composes shots more than one would expect

considering the static camera set-ups and shows us characters glimpsed and

locations that are only glimpsed through the frame of the carís windows. The

quality of the acting is uniformly stellar. Itís nearly impossible for a

casual viewer to guess the amount of training that the actors have had, since

they all deliver their performances in the same convincingly unmannered manner.

If Ten feels neither like a reinvention of cinema nor a truly

fundamentalist attempt to get back to basics, it manages to work best as a

distinctive entry in Kiarostamiís diverse oeuvre. Fans of the director will find

more to like in it than casual samplers, I imagine, but even those wholly

unacquainted with his work should find it hard to deny the emotional pull that

such proximity to characters creates.

The achievements of Ten are considerable enough to

outweigh even such a major quibble as that, however. Kiarostamiís use of

off-screen space to enhance the world his films take place in is as adroit as

ever here. Although this movie sometimes seems randomly put together, thereís a fair

amount of craft on display. Kiarostami uses jump cuts to compress what still

feels like real time. He also composes shots more than one would expect

considering the static camera set-ups and shows us characters glimpsed and

locations that are only glimpsed through the frame of the carís windows. The

quality of the acting is uniformly stellar. Itís nearly impossible for a

casual viewer to guess the amount of training that the actors have had, since

they all deliver their performances in the same convincingly unmannered manner.

If Ten feels neither like a reinvention of cinema nor a truly

fundamentalist attempt to get back to basics, it manages to work best as a

distinctive entry in Kiarostamiís diverse oeuvre. Fans of the director will find

more to like in it than casual samplers, I imagine, but even those wholly

unacquainted with his work should find it hard to deny the emotional pull that

such proximity to characters creates.

* * *

10-08-02

Jeremy Heilman