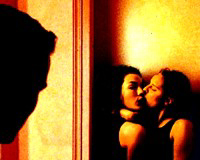

Secret Things (Jean-Claude

Brisseau, 2002)

Equal parts Olivier Assays’ demonlover and Howard Hawks’ Gentlemen

Prefer Blondes, Jean-Claude Brisseau’s Secret

Things is an exaggerated fable of sexual politics and comic elegance. Filled

with one jaw-dropping sequence after another, each one elevating the stakes in

its fiercely competitive battle of the sexes, Secret Things assumes hilariously operatic dimensions by the time it

reaches its third act, and only grows more audacious from there. The opening

scene’s cock-tease and the revelation of the audience that follows accurately

suggest that the film will gladly leave logic at the door if it might better

provoke, and provoke it does. Telling the story of an unlikely friendship of two

seemingly opposite women as they fuck their way to the top of the social ladder,

Secret Things might not be politically

correct, or even that relevant to the real world, but it certainly addresses

(and possibly indulges in) a certain type of male fantasy that is all too common

in cinema.

Equal parts Olivier Assays’ demonlover and Howard Hawks’ Gentlemen

Prefer Blondes, Jean-Claude Brisseau’s Secret

Things is an exaggerated fable of sexual politics and comic elegance. Filled

with one jaw-dropping sequence after another, each one elevating the stakes in

its fiercely competitive battle of the sexes, Secret Things assumes hilariously operatic dimensions by the time it

reaches its third act, and only grows more audacious from there. The opening

scene’s cock-tease and the revelation of the audience that follows accurately

suggest that the film will gladly leave logic at the door if it might better

provoke, and provoke it does. Telling the story of an unlikely friendship of two

seemingly opposite women as they fuck their way to the top of the social ladder,

Secret Things might not be politically

correct, or even that relevant to the real world, but it certainly addresses

(and possibly indulges in) a certain type of male fantasy that is all too common

in cinema.

After the manager at the club the two of them work at tries

to promote himself to pimp, man-eating stripper Nathalie (Coralie Revel) and

timid barmaid Sandrine (Sabrina Seyvecou) quit their jobs and quickly befriend

one another. Sandrine confesses that she’s long admired Nathalie’s ability

to pleasure herself in front of a crowd, and soon an under-the-cover

masturbation session becomes Sandrine’s debut, of sorts. The two quickly begin

upping the ante by walking the streets naked but for long jackets and by

pleasuring themselves in front of strangers. Masturbation here becomes an ends

to a means; a stimulant devised to ensnare those that take pleasure in watching

the act, and one could suggest that Brisseau employs similar tactics with his

audience. By the time the women apply their techniques to the game of corporate

ladder-climbing, the film has become a challenging examination of gender

relationships. Self-pleasure begins as self-realization here and onanism is a

form of empowerment, but it soon becomes obvious how the seemingly harmless sex

games that are played are part of a larger power-struggle. The moment a man

realizes a woman is playing with herself on a subway platform, the mood shifts,

both between the characters and the audience members watching the film.

Suddenly, this harmless exhibitionism is making suppositions on behalf of the

voyeur. To put it more succinctly, self-abuse grants power to these women, who

promptly begin to abuse that power. As the women rise in ranks, they grow

bolder, and the games that they play only take on a greater charge.

After the manager at the club the two of them work at tries

to promote himself to pimp, man-eating stripper Nathalie (Coralie Revel) and

timid barmaid Sandrine (Sabrina Seyvecou) quit their jobs and quickly befriend

one another. Sandrine confesses that she’s long admired Nathalie’s ability

to pleasure herself in front of a crowd, and soon an under-the-cover

masturbation session becomes Sandrine’s debut, of sorts. The two quickly begin

upping the ante by walking the streets naked but for long jackets and by

pleasuring themselves in front of strangers. Masturbation here becomes an ends

to a means; a stimulant devised to ensnare those that take pleasure in watching

the act, and one could suggest that Brisseau employs similar tactics with his

audience. By the time the women apply their techniques to the game of corporate

ladder-climbing, the film has become a challenging examination of gender

relationships. Self-pleasure begins as self-realization here and onanism is a

form of empowerment, but it soon becomes obvious how the seemingly harmless sex

games that are played are part of a larger power-struggle. The moment a man

realizes a woman is playing with herself on a subway platform, the mood shifts,

both between the characters and the audience members watching the film.

Suddenly, this harmless exhibitionism is making suppositions on behalf of the

voyeur. To put it more succinctly, self-abuse grants power to these women, who

promptly begin to abuse that power. As the women rise in ranks, they grow

bolder, and the games that they play only take on a greater charge.

In Secret Things, everyone’s

so forthright about their sexual proclivities and mindgames that the movie

scarcely has subtext. At one point early in the film, Nathalie blithely recalls

how her mother compared the battle of the sexes to the class struggle.

Inevitably, the story moves in that direction as it develops. The elaborate plan

hatched by the two women early on to use their sexual prowess and smarts to rise

in stature is explained in detail, and much of the film details, almost

predictably, how that plan comes to fruition. Of course, Brisseau tosses in a

few surprises, and the sense of danger grows more tenable as the stakes are

raised. Real tension begins to emerge once Christophe (Fabrice Deville) enters

the scene. Presented as the women’s ultimate target, this rich playboy

incessantly uses women, apparently breaking them to the point where they

immolate themselves. As Nathalie and Sandrine move into his world, the movie

grows increasingly baroque. Two sequences, one featuring incest by proxy, the

other an orgy similar to the one in Eyes

Wide Shut, especially hammer home the class differences that exist here, if

only because their level of perversity seems beyond those who have to concern

themselves with worldly pursuits. The great joke of the movie is that he’s no

different than bar owner in the film’s first sequence who wants the two women

to whore themselves to a customer, except in that he has the power to turn his

fantasies into reality. Furthermore, as appalling as Christophe is, there’s no

escaping the feeling that Nathalie and Sandrine’s attempts to use sex to

reduce him to their pawn are just as vindictive. When Secret Things ends, it appropriately questions what it is that these

women are really after and if they’ve achieved anything at all.

In Secret Things, everyone’s

so forthright about their sexual proclivities and mindgames that the movie

scarcely has subtext. At one point early in the film, Nathalie blithely recalls

how her mother compared the battle of the sexes to the class struggle.

Inevitably, the story moves in that direction as it develops. The elaborate plan

hatched by the two women early on to use their sexual prowess and smarts to rise

in stature is explained in detail, and much of the film details, almost

predictably, how that plan comes to fruition. Of course, Brisseau tosses in a

few surprises, and the sense of danger grows more tenable as the stakes are

raised. Real tension begins to emerge once Christophe (Fabrice Deville) enters

the scene. Presented as the women’s ultimate target, this rich playboy

incessantly uses women, apparently breaking them to the point where they

immolate themselves. As Nathalie and Sandrine move into his world, the movie

grows increasingly baroque. Two sequences, one featuring incest by proxy, the

other an orgy similar to the one in Eyes

Wide Shut, especially hammer home the class differences that exist here, if

only because their level of perversity seems beyond those who have to concern

themselves with worldly pursuits. The great joke of the movie is that he’s no

different than bar owner in the film’s first sequence who wants the two women

to whore themselves to a customer, except in that he has the power to turn his

fantasies into reality. Furthermore, as appalling as Christophe is, there’s no

escaping the feeling that Nathalie and Sandrine’s attempts to use sex to

reduce him to their pawn are just as vindictive. When Secret Things ends, it appropriately questions what it is that these

women are really after and if they’ve achieved anything at all.

80

02-20-04

Jeremy Heilman