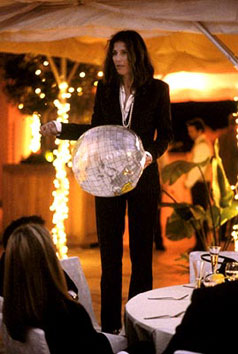

Full Frontal (Steven Soderbergh) 2002

Full Frontal, the latest film from Steven

Soderbergh, the American filmmaker who seems most stuck between the realms of

independent genius and studio hack (or is that independent hack and studio

genius?), has him directly confronting the disconnect between those two modes of

his filmmaking. Set in Hollywood, and revolving around the people we hate who

make the movies that we love, this movie, which was shot with a hand-held

digital camera, is intercut with segments from Rendezvous, a similarly

self-reflexive film within the film, which has been shot on actual celluloid

with a formalistic treatment. This treatment sets up in the audience a

questioning of reality that much of the dialogue scenes in the film explicitly

and implicitly address. Besides the obvious use of two mediums, there are clever

scenes like the one that shows us characters creating their “porno names”

juxtaposed against the testimonials of a masseuse that actually uses an assumed

name when working with her clients (and when she chats online). For a while, the

movie hums along with a surprisingly offhand and chaotic style, and you think

that it might be building to a genuinely revolutionary point, but it

unfortunately loses itself along the way, and descends into a series of

inconsistently giggle-worthy, but consistently empty skits.

Full Frontal, the latest film from Steven

Soderbergh, the American filmmaker who seems most stuck between the realms of

independent genius and studio hack (or is that independent hack and studio

genius?), has him directly confronting the disconnect between those two modes of

his filmmaking. Set in Hollywood, and revolving around the people we hate who

make the movies that we love, this movie, which was shot with a hand-held

digital camera, is intercut with segments from Rendezvous, a similarly

self-reflexive film within the film, which has been shot on actual celluloid

with a formalistic treatment. This treatment sets up in the audience a

questioning of reality that much of the dialogue scenes in the film explicitly

and implicitly address. Besides the obvious use of two mediums, there are clever

scenes like the one that shows us characters creating their “porno names”

juxtaposed against the testimonials of a masseuse that actually uses an assumed

name when working with her clients (and when she chats online). For a while, the

movie hums along with a surprisingly offhand and chaotic style, and you think

that it might be building to a genuinely revolutionary point, but it

unfortunately loses itself along the way, and descends into a series of

inconsistently giggle-worthy, but consistently empty skits.

While watching Full Frontal, a host of

inconsistencies crop up. It doesn’t help matters that the film-within-the-film

Rendezvous isn’t for a moment believable as an actual Hollywood

production (but then again, neither is the David Fincher-directed

film-within-the-film-within-the-film). Its corny symbolism and dopey dialogue

really only make sense in the context of those “non-movie” scenes that

surround them. It seems to consist mostly of long dialogue sequences between an

actor and a reporter discussing the state of the black man in mainstream

American cinema. Such a stance coming from Steven Soderbergh placed in the mouth

of Julia Roberts feels like some sort of apology, since neither of them has an

excellent track record in their onscreen relationships with black actors. Full

Frontal explicitly brings up Julia’s chaste romance with Denzel Washington

in The Pelican Brief, but doesn’t mention the scene in Traffic

where a young girl’s sexual encounter with a black drug dealer is presented as

her worst imaginable offense. When it comes time to show a hot and heavy

interracial sex scene between two of the characters, though, Soderbergh shifts

his focus until it’s an abstraction, foisting a joke onto the audience that

makes them question his sincerity. You start to question the reality of the

framing device as well though, since its relationships are as constructed as the

ones in the movie, and when it starts pushing toward a big Hollywood ending,

Soderbergh attempts to salvage everything by telling you that it’s all a movie

and that none of it mattered.

While watching Full Frontal, a host of

inconsistencies crop up. It doesn’t help matters that the film-within-the-film

Rendezvous isn’t for a moment believable as an actual Hollywood

production (but then again, neither is the David Fincher-directed

film-within-the-film-within-the-film). Its corny symbolism and dopey dialogue

really only make sense in the context of those “non-movie” scenes that

surround them. It seems to consist mostly of long dialogue sequences between an

actor and a reporter discussing the state of the black man in mainstream

American cinema. Such a stance coming from Steven Soderbergh placed in the mouth

of Julia Roberts feels like some sort of apology, since neither of them has an

excellent track record in their onscreen relationships with black actors. Full

Frontal explicitly brings up Julia’s chaste romance with Denzel Washington

in The Pelican Brief, but doesn’t mention the scene in Traffic

where a young girl’s sexual encounter with a black drug dealer is presented as

her worst imaginable offense. When it comes time to show a hot and heavy

interracial sex scene between two of the characters, though, Soderbergh shifts

his focus until it’s an abstraction, foisting a joke onto the audience that

makes them question his sincerity. You start to question the reality of the

framing device as well though, since its relationships are as constructed as the

ones in the movie, and when it starts pushing toward a big Hollywood ending,

Soderbergh attempts to salvage everything by telling you that it’s all a movie

and that none of it mattered.

This move seems calculated to piss off the audience, and I

imagine that for many people it worked, but mostly I was just left disappointed

that a director who seems as perceptive as Soderbergh couldn’t make a more

analytical statement about the reality of movies. Instead, he simply asks us to

let him off the hook for even attempting to tell a story in such an inadequate

medium and criticizes our naiveté for getting involved in the process of

watching this one. I suppose that sort of fourth-wall shattering moment is

supposed to be wild, and in a dramatic Hollywood film it might be, but since

this film announces itself so loudly as an experimental, quirky indie, you

can’t help but expect more of a result from the director’s experiments.

That’s not to say that Full Frontal is a total wash. I found several of

its comic skits to be funny, most notably those involving Catherine Keener, who

transcends her clichéd bitchy studio exec character’s limitations here with

her performance. She’s the one thing in the movie that really feels like

it’s operating without a net. Nicky Katt’s scenes where he plays an actor

impersonating Hitler, however, seemed as funny to me as genocide. Many

viewers’ reactions will probably differ greatly here, though, since the movie

throws so many disparate elements together. It’s as difficult to imagine

someone who will find nothing to like in Full Frontal as it is to

conceive of someone who can embrace everything it offers. It’s a film that’s too

wildly pieced together to inspire either knee-jerk admiration or derision.

This move seems calculated to piss off the audience, and I

imagine that for many people it worked, but mostly I was just left disappointed

that a director who seems as perceptive as Soderbergh couldn’t make a more

analytical statement about the reality of movies. Instead, he simply asks us to

let him off the hook for even attempting to tell a story in such an inadequate

medium and criticizes our naiveté for getting involved in the process of

watching this one. I suppose that sort of fourth-wall shattering moment is

supposed to be wild, and in a dramatic Hollywood film it might be, but since

this film announces itself so loudly as an experimental, quirky indie, you

can’t help but expect more of a result from the director’s experiments.

That’s not to say that Full Frontal is a total wash. I found several of

its comic skits to be funny, most notably those involving Catherine Keener, who

transcends her clichéd bitchy studio exec character’s limitations here with

her performance. She’s the one thing in the movie that really feels like

it’s operating without a net. Nicky Katt’s scenes where he plays an actor

impersonating Hitler, however, seemed as funny to me as genocide. Many

viewers’ reactions will probably differ greatly here, though, since the movie

throws so many disparate elements together. It’s as difficult to imagine

someone who will find nothing to like in Full Frontal as it is to

conceive of someone who can embrace everything it offers. It’s a film that’s too

wildly pieced together to inspire either knee-jerk admiration or derision.

* *

08-04-02

Jeremy Heilman