Femme Fatale (Brian DePalma) 2002

Brian DePalma’s Femme

Fatale is an odd, fascinating movie. Few films flirt so audaciously with

genuine ideas only to present their most obvious pleasures in the superficial.

It’s tough to decide if DePalma is incapable of a more in-depth probing of his

subject matter here, which most prominently investigates the objectification and

empowerment of women, or if he’s simply not willing to do so in a typically

didactic, speech-laden way. There

are a multitude of themes running throughout, most of which have surfaced in the

director’s previous work, and most of them are conveyed mainly in visual terms

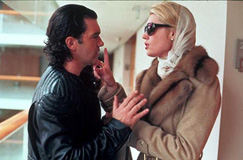

with rhyming images and tracking shot connections. The opening scene, for

example, links the Barbara Stanwyck character (quite arguably the prototype for

the modern femme fatale) from the Billy Wilder classic Double Indemnity with Laure (Rebecca Romijn-Stamos), the film’s

protagonist, creating a sexist, absurd audience expectation of her behavior that

the rest of the film spends attempting to triumphantly brush off.

Brian DePalma’s Femme

Fatale is an odd, fascinating movie. Few films flirt so audaciously with

genuine ideas only to present their most obvious pleasures in the superficial.

It’s tough to decide if DePalma is incapable of a more in-depth probing of his

subject matter here, which most prominently investigates the objectification and

empowerment of women, or if he’s simply not willing to do so in a typically

didactic, speech-laden way. There

are a multitude of themes running throughout, most of which have surfaced in the

director’s previous work, and most of them are conveyed mainly in visual terms

with rhyming images and tracking shot connections. The opening scene, for

example, links the Barbara Stanwyck character (quite arguably the prototype for

the modern femme fatale) from the Billy Wilder classic Double Indemnity with Laure (Rebecca Romijn-Stamos), the film’s

protagonist, creating a sexist, absurd audience expectation of her behavior that

the rest of the film spends attempting to triumphantly brush off.

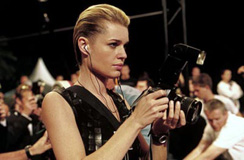

After establishing the grounds for his thesis, DePalma,

with his usual brazen bravado, allows us the fun of watching Laure test out the

mold that Stanwyck has made. By hilariously parodying the overblown secret-agent

antics of his own Mission: Impossible,

he casts Laure into the suddenly stereotypical Laura Craft female action hero

mode, pushing both her sexuality and capability for deception farther than any

other director might dare. Powered by a dreamy, floating camera, lesbian

wish-fulfillment, and more phallic symbolism than you can shake a stick at, the

sequence is a hackneyed male fantasy cum reality through the magic of the

movies. It’s the anachronistic Cannes 2001 setting (where East-West is oddly playing and the more appropriate choice of Mulholland

Dr. oddly isn’t) of this heist that most heavily clues the audience into

the movie’s other prime concern, which is an examination of the layers that

exist, or don’t, between fantasy and reality.

Even in this relatively inconsequential, but thrilling, opening sequence,

he tests the audience’s ability to accept coincidence and contrivance as he

crafts an intricate web of narrative event for Laure to steer herself through on

the road to some sort of liberation.

After establishing the grounds for his thesis, DePalma,

with his usual brazen bravado, allows us the fun of watching Laure test out the

mold that Stanwyck has made. By hilariously parodying the overblown secret-agent

antics of his own Mission: Impossible,

he casts Laure into the suddenly stereotypical Laura Craft female action hero

mode, pushing both her sexuality and capability for deception farther than any

other director might dare. Powered by a dreamy, floating camera, lesbian

wish-fulfillment, and more phallic symbolism than you can shake a stick at, the

sequence is a hackneyed male fantasy cum reality through the magic of the

movies. It’s the anachronistic Cannes 2001 setting (where East-West is oddly playing and the more appropriate choice of Mulholland

Dr. oddly isn’t) of this heist that most heavily clues the audience into

the movie’s other prime concern, which is an examination of the layers that

exist, or don’t, between fantasy and reality.

Even in this relatively inconsequential, but thrilling, opening sequence,

he tests the audience’s ability to accept coincidence and contrivance as he

crafts an intricate web of narrative event for Laure to steer herself through on

the road to some sort of liberation.

Since Femme Fatale presents

Laure’s moral discovery without betraying the rules of the suspense film, it

never feels too earnest or cloying. Instead it comes off as a simultaneous

celebration of the potential of the genre to thrill and a justification for what

compels him to work in it. Throughout Femme

Fatale, DePalma, per usual, references many other movies, but the nods that

have the most impact are the allusions to his own work. The scene where Laure is

followed to a hotel explicitly recalls a similar moment in his Body

Double (itself reminiscent of Hitchcock’s Rear

Window). The split-screen technique used in several sequences, in which the

camera is literally torn into two because it’s equally interested in the

voyeur and the subject of voyeurism, echoes his early film Sisters.

A graphic, slow-motion impalement seems to have been lifted from his Raising

Cain. The cumulative effect of these references when coupled with Laure’s

redemption through exploitation, turn the film into an exciting game of

self-observation for DePalma. The movie leaves a strong impression that DePalma

sees his willingness to deal with the issues in his films as a sort of cathartic

release that keeps him from feeling compelled to explore them in reality.

Filmmaking allows him to act out his wildest fantasies just as Laure is allowed

to temporarily toy with the mantle of the femme fatale in this movie. Perhaps

more than any film he’s made up to this point, Femme Fatale is

DePalma’s most humanistic defense of his body of work, but only a director with

his unique obsessions and talents could make a statement of humanism that’s so

provocative, sexy, and exciting.

Since Femme Fatale presents

Laure’s moral discovery without betraying the rules of the suspense film, it

never feels too earnest or cloying. Instead it comes off as a simultaneous

celebration of the potential of the genre to thrill and a justification for what

compels him to work in it. Throughout Femme

Fatale, DePalma, per usual, references many other movies, but the nods that

have the most impact are the allusions to his own work. The scene where Laure is

followed to a hotel explicitly recalls a similar moment in his Body

Double (itself reminiscent of Hitchcock’s Rear

Window). The split-screen technique used in several sequences, in which the

camera is literally torn into two because it’s equally interested in the

voyeur and the subject of voyeurism, echoes his early film Sisters.

A graphic, slow-motion impalement seems to have been lifted from his Raising

Cain. The cumulative effect of these references when coupled with Laure’s

redemption through exploitation, turn the film into an exciting game of

self-observation for DePalma. The movie leaves a strong impression that DePalma

sees his willingness to deal with the issues in his films as a sort of cathartic

release that keeps him from feeling compelled to explore them in reality.

Filmmaking allows him to act out his wildest fantasies just as Laure is allowed

to temporarily toy with the mantle of the femme fatale in this movie. Perhaps

more than any film he’s made up to this point, Femme Fatale is

DePalma’s most humanistic defense of his body of work, but only a director with

his unique obsessions and talents could make a statement of humanism that’s so

provocative, sexy, and exciting.

* * * *

11-14-02

Jeremy Heilman