Auto Focus (Paul Schrader) 2002

Thereís at least one scene in Paul Schraderís Auto

Focus thatís sure to have die hard auteurists in a state of rapture. In it

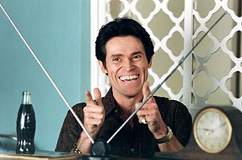

Bob Crane (Greg Kinnear), church-going amateur pornographer and television star,

has a conference in a diner with his priest about his new tendency to swing by

the strip bar at night after a long day of filming ďHoganís HeroesĒ.

Midway through the conversation, which illustrates Craneís chipper inability

to recognize how far from ďnormalĒ heís drifted, a female fan passing by

asks for a souvenir snapshot to commemorate meeting the star, and Crane asks the

priest to take the photo. Suddenly, and quite ignorantly, Crane is implicating

his religion in his sin. Though Auto Focus is less a journey toward

salvation than most of Schraderís other films, itís impossible not to notice

the possibility of it at this moment. This meeting with the clergyman is perhaps

the only moment in the film where Kinnearís Crane seems to have much of a

soul, and even then itís fleeting. His depth doesnít even last for the

entire scene. For the rest of the film, Crane seems to be patching holes in the

sinking ship that is his life. Most of his decisions are wishy washy at best,

and contradictory at worst. Heís far less concerned with the long-term effects

of his actions than the short-term pleasures of them, and with that inherent

shortsightedness he seems perfect fodder for a cautionary tale about the shifts

in morality, both inside and outside Hollywood, during the Sixties and

Seventies.

Thereís at least one scene in Paul Schraderís Auto

Focus thatís sure to have die hard auteurists in a state of rapture. In it

Bob Crane (Greg Kinnear), church-going amateur pornographer and television star,

has a conference in a diner with his priest about his new tendency to swing by

the strip bar at night after a long day of filming ďHoganís HeroesĒ.

Midway through the conversation, which illustrates Craneís chipper inability

to recognize how far from ďnormalĒ heís drifted, a female fan passing by

asks for a souvenir snapshot to commemorate meeting the star, and Crane asks the

priest to take the photo. Suddenly, and quite ignorantly, Crane is implicating

his religion in his sin. Though Auto Focus is less a journey toward

salvation than most of Schraderís other films, itís impossible not to notice

the possibility of it at this moment. This meeting with the clergyman is perhaps

the only moment in the film where Kinnearís Crane seems to have much of a

soul, and even then itís fleeting. His depth doesnít even last for the

entire scene. For the rest of the film, Crane seems to be patching holes in the

sinking ship that is his life. Most of his decisions are wishy washy at best,

and contradictory at worst. Heís far less concerned with the long-term effects

of his actions than the short-term pleasures of them, and with that inherent

shortsightedness he seems perfect fodder for a cautionary tale about the shifts

in morality, both inside and outside Hollywood, during the Sixties and

Seventies.

Thatís not to imply Auto Focus is a perfect

example of its genre. For starters, the decision to portray the sex in the film

as a fun diversion instead of an indicator of a twisted obsession rips most of

the danger out of the scenario. If hard-core pornography isnít whatís called

for here, at least one glimpse of full-frontal male nudity would have helped

sell the reality of the sex scenes, since as the theyíre presented, you

canít help but feel that theyíre mostly preoccupied with hiding the

actorsí genitalia. Before long, the compositions end up feeling like something

out of Austin Powers movie, and thatís hardly the desired effect, since

the footage is supposed to have been randomly captured by amateurs. The only

moment in Auto Focus where the sex feels truly taboo is during an episode

that makes Crane reassert his sexuality. Furthermore, Schraderís directorial

approach, in which he gradually bleaches out the film stock, replaces pop songs

with Angelo Badalamentiís score, and increases the shakiness of the camera is

meant to parallel the emotional and moral decline of Crane, but it often

overpowers and leaps ahead of it. Kinnear is better here than heís ever been

thanks to his ample, dopey charm, even if heís more likable in the voiceovers

than he is during the filmís action, and you wish you could judge his

performance on its own terms instead of on the styleís. Willem Dafoe plays

John Carpenter, the videophile who introduces Crane to the gadgets that become

his true obsession, and his performance is a match for Kinnearís. The scenes

they share are wonderfully written and make for most of the movieís

highlights.

Thatís not to imply Auto Focus is a perfect

example of its genre. For starters, the decision to portray the sex in the film

as a fun diversion instead of an indicator of a twisted obsession rips most of

the danger out of the scenario. If hard-core pornography isnít whatís called

for here, at least one glimpse of full-frontal male nudity would have helped

sell the reality of the sex scenes, since as the theyíre presented, you

canít help but feel that theyíre mostly preoccupied with hiding the

actorsí genitalia. Before long, the compositions end up feeling like something

out of Austin Powers movie, and thatís hardly the desired effect, since

the footage is supposed to have been randomly captured by amateurs. The only

moment in Auto Focus where the sex feels truly taboo is during an episode

that makes Crane reassert his sexuality. Furthermore, Schraderís directorial

approach, in which he gradually bleaches out the film stock, replaces pop songs

with Angelo Badalamentiís score, and increases the shakiness of the camera is

meant to parallel the emotional and moral decline of Crane, but it often

overpowers and leaps ahead of it. Kinnear is better here than heís ever been

thanks to his ample, dopey charm, even if heís more likable in the voiceovers

than he is during the filmís action, and you wish you could judge his

performance on its own terms instead of on the styleís. Willem Dafoe plays

John Carpenter, the videophile who introduces Crane to the gadgets that become

his true obsession, and his performance is a match for Kinnearís. The scenes

they share are wonderfully written and make for most of the movieís

highlights.

If Auto Focus never completely loses view of its

subject, it also never really gets a sharp look at him either. As the movie

moves into its second hour, and stresses the pathetic existence of the B-list

celebrity, it grows glum and loses much of the sly wit that made it so enjoyable

in the first half. As Schrader starts to tell us that Crane will never ďget

itĒ, we begin to question the point of the movie. Surely it isnít revelatory

to point out that with power comes the temptation to abuse that power.

Schraderís frequent hints that weíre meant to look at Bob Crane as a product

of his society (he trots out hippies and introduces color videotapes as Crane

slides deeper into debauchery) remind us both of the televisionís invasion

into the American home and the further invasions of privacy that video age will

bring, but he doesnít seem to have a real opinion about them. This version of

Crane seems a rather inconsequential figure on which to hang bold statements

about America. If Auto Focus fails to be the truly great statement that

it obviously yearns to be, it canít be faulted much for trying, since most of

its failures on that account arise from its desire to remain honest about its

subject's limitations. As a movie-of-the-week style romp through a celebrityís

garbage can, though, itís not half bad.

If Auto Focus never completely loses view of its

subject, it also never really gets a sharp look at him either. As the movie

moves into its second hour, and stresses the pathetic existence of the B-list

celebrity, it grows glum and loses much of the sly wit that made it so enjoyable

in the first half. As Schrader starts to tell us that Crane will never ďget

itĒ, we begin to question the point of the movie. Surely it isnít revelatory

to point out that with power comes the temptation to abuse that power.

Schraderís frequent hints that weíre meant to look at Bob Crane as a product

of his society (he trots out hippies and introduces color videotapes as Crane

slides deeper into debauchery) remind us both of the televisionís invasion

into the American home and the further invasions of privacy that video age will

bring, but he doesnít seem to have a real opinion about them. This version of

Crane seems a rather inconsequential figure on which to hang bold statements

about America. If Auto Focus fails to be the truly great statement that

it obviously yearns to be, it canít be faulted much for trying, since most of

its failures on that account arise from its desire to remain honest about its

subject's limitations. As a movie-of-the-week style romp through a celebrityís

garbage can, though, itís not half bad.

* * *

10-06-02

Jeremy Heilman