Cremaster 2 (Matthew Barney, 1999)

Easily the most plot-driven in all of Matthew Barney’s

Cremaster cycle, Cremaster 2 still

conveys the thematic obsessions that drive the series, and stands as one of its

most accessible entries. The very first image in the film is a close-up of a

glass-covered saddle that’s been suspended in midair with its straps

levitating above its seat. Barney films this saddle at first so that it looks

like an ovular symbol, but as his camera slowly zooms out, its true identity as

an emblem of masculinity is revealed. The biological conversion from a feminine

state to a masculine state that began in Cremaster

1 continues insistently here and the dominant emotion that hangs over the

film is a lament for the return to a period before a Y chromosome entered into

the organism, to a peaceful ungendered state.

Easily the most plot-driven in all of Matthew Barney’s

Cremaster cycle, Cremaster 2 still

conveys the thematic obsessions that drive the series, and stands as one of its

most accessible entries. The very first image in the film is a close-up of a

glass-covered saddle that’s been suspended in midair with its straps

levitating above its seat. Barney films this saddle at first so that it looks

like an ovular symbol, but as his camera slowly zooms out, its true identity as

an emblem of masculinity is revealed. The biological conversion from a feminine

state to a masculine state that began in Cremaster

1 continues insistently here and the dominant emotion that hangs over the

film is a lament for the return to a period before a Y chromosome entered into

the organism, to a peaceful ungendered state.

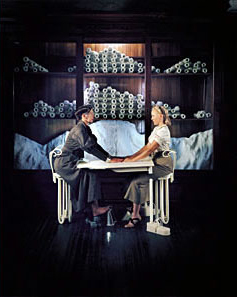

That desire to overcome biological constraints powers the

narrative, which intertwines the stories of convicted murderer Gary Gilmore and

his rumored grandfather Harry Houdini (played by Norman Mailer, the author who

wrote “The Executioner’s Song”, based on Gilmore’s life). After

introducing several of the film’s dominant symbols (the saddle, bees, and the

Utah landscape), the film’s story kicks off with an imagined meeting of

Gilmore’s parents and Baby Fay La Foe, Houdini’s lover. Seated at a table

across from each other, they begin an unknowable ritual that culminates in the

metaphorical conception of Gilmore. The bee-influenced imagery in this sequence,

such as the thorax-like waistlines, the beehives (which bear more than a passing

resemblance to the Guggenheim museum, which plays a more dominant role in the

film series), the honeycombs, and the drop of honey that inseminates Gilmore’s

mother, all conspire to place Gilmore’s eventual transgression into context.

The murders that he commits seem to be at least partially borne out of a brand

of masculine aggression that the film argues is inherent in the Utah (the

Beehive State, incidentally) that he calls home. The next sequence, which

features a mixture of bees and heavy metal dramatizes that rage and shows a

healthy, but still unnerving, form of its expression. The credits reveal that

the musicians here are simultaneous incarnations of musician Johnny Cash

(similar to the simultaneous incarnations of Goodyear in Cremaster 1), the country-rock singer who placed a call to Gilmore

before he was executed, at the killer’s request.

After attempting to convey at least part of Gilmore’s

emotional state, the film finally shows the man himself, played by Barney

himself, as he sits at a service station in a contraption built from two

interconnected cars (recalling Cremaster 1’s

twin blimps, but with a decidedly masculine twist). Instead of being the angry,

aggressive figure that one would expect, however, Barney’s Gilmore is clearly

struck by a sense of longing. The real Gilmore supposedly committed murder in attempt to

win the attentions of his estranged girlfriend, Nicole Baker. The

estrangement that he feels seems to be metaphorically in touch with the longing for a return to the sexually undifferentiated state of the

first Cremaster film that feels present in the harsh imagery of Cremaster

2. The rift between female and male that’s created in all of

us when we become one or the other becomes something potentially violent here. In a

languorous attempt to sculpt using his environment and express his frustration

through art, Gilmore is seen ripping at the moldings of the car he’s in and

forming them into art, but that attempt is fruitless and eventually results in

destructive behavior. He’s seen remembering the girl he can’t have, flashes

a tiny, undeveloped penis, and then gets a gun from the same glove box from

which he had previously gotten the Vaseline used in his aborted sculpture,

showing how tenuous the line between constructive and harmful behaviors can be

and how both can be fueled by the same motivations. He finally gets out of the

car to commit a robbery and homicide, and the soundtrack shifts. The soothing

ballad that Baker was singing is mixed with a violent droning of bees, providing

an aural insight into his dual motivations as he executes his victim.

After attempting to convey at least part of Gilmore’s

emotional state, the film finally shows the man himself, played by Barney

himself, as he sits at a service station in a contraption built from two

interconnected cars (recalling Cremaster 1’s

twin blimps, but with a decidedly masculine twist). Instead of being the angry,

aggressive figure that one would expect, however, Barney’s Gilmore is clearly

struck by a sense of longing. The real Gilmore supposedly committed murder in attempt to

win the attentions of his estranged girlfriend, Nicole Baker. The

estrangement that he feels seems to be metaphorically in touch with the longing for a return to the sexually undifferentiated state of the

first Cremaster film that feels present in the harsh imagery of Cremaster

2. The rift between female and male that’s created in all of

us when we become one or the other becomes something potentially violent here. In a

languorous attempt to sculpt using his environment and express his frustration

through art, Gilmore is seen ripping at the moldings of the car he’s in and

forming them into art, but that attempt is fruitless and eventually results in

destructive behavior. He’s seen remembering the girl he can’t have, flashes

a tiny, undeveloped penis, and then gets a gun from the same glove box from

which he had previously gotten the Vaseline used in his aborted sculpture,

showing how tenuous the line between constructive and harmful behaviors can be

and how both can be fueled by the same motivations. He finally gets out of the

car to commit a robbery and homicide, and the soundtrack shifts. The soothing

ballad that Baker was singing is mixed with a violent droning of bees, providing

an aural insight into his dual motivations as he executes his victim.

At this point, Cremaster

2 plunges back into abstraction. Shots showing the murder scene are intercut

with ones that move through an empty cathedral toward the perfoming Mormon

Tabernacle Choir. This sequence seems to represent a moment of near-religious

clarity for Gilmore (and an ironic one since both of Gilmore’s victims were

Mormon). He seems to grasp here the idea of transcendence that had eluded him

previously. In real life Gary Gilmore opted not to appeal his death sentence, an

unheard of decision that essentially busted the legal system when it prompted a

series of legal appeals made on his behalf against his will. Barney doesn’t

include any legal wrangling in Cremaster 2, but he does seem to suggest that Gilmore’s decision

to not fight the day he was appointed to die on is his way of taking his fate

into his own hands, and in a way, transcending the death through gaining some

loose form of power over it. Throughout the film until this point, Gilmore is

presented as something of a drone, unable to overcome his biologically imposed

frustrations, but in this decision, he seems to gain some form of respect for

Barney and the depictions of him shift from pathetic and uncertain to iconic.

This depiction of Gilmore is certainly the most morally questionable sequence in

the Cremaster cycle, but at the same time it also is one of the most emotionally

affecting.

In reality, Gilmore chose to be executed by a firing squad,

but in Barney’s alternate vision of the events, he is put to death during a

bizarre ritual that only underlines the savagery of the sanctioned killing and

connects the justification of it with the motives that inspired the original

crime. The convict Gilmore is led to a bizarre, beehive-adorned arena on the

Utah Salt Plains that recalls the football field from Cremaster 1. Prior to his arrival, horse-riding guards move in

symmetrical patterns that bring to mind the dance patterns of the Berkeley

dancers from that film. Gilmore is made to wear a ceremonial belt buckle

(bearing the bisected oval that serves as the Cremaster series’ logo) and

outfit before he gets on a wild bull. Without any exchange of dialogue, the

ritual continues as Gilmore situates himself on the buffalo and grasps the

saddle strap and rope. The macabre ceremony continues as he rides the stampeding

animal into the arena, and continues to ride until both die from exhaustion.

In reality, Gilmore chose to be executed by a firing squad,

but in Barney’s alternate vision of the events, he is put to death during a

bizarre ritual that only underlines the savagery of the sanctioned killing and

connects the justification of it with the motives that inspired the original

crime. The convict Gilmore is led to a bizarre, beehive-adorned arena on the

Utah Salt Plains that recalls the football field from Cremaster 1. Prior to his arrival, horse-riding guards move in

symmetrical patterns that bring to mind the dance patterns of the Berkeley

dancers from that film. Gilmore is made to wear a ceremonial belt buckle

(bearing the bisected oval that serves as the Cremaster series’ logo) and

outfit before he gets on a wild bull. Without any exchange of dialogue, the

ritual continues as Gilmore situates himself on the buffalo and grasps the

saddle strap and rope. The macabre ceremony continues as he rides the stampeding

animal into the arena, and continues to ride until both die from exhaustion.

At this point, the film begins to cut to shots showing

Harry Houdini as he is encased in a honeycomb-shaped chamber as he begins one of

his escape routines. Houdini’s attempts to escape his physical constraints are

compared with Gilmore’s decision to opt out of the appeal process here. The

camera begins retreating away from the arena, and another series of landscape

shots are shown. The saddle from the start of the film makes another appearance,

this time with a duo of dancers doing a two-step around it. The unspoken

impression here is one of an eternal, Rorschach blotch of a landscape, resulting

in a genuinely thrilling Koyaanisqatsi-style

moment as the film regresses backward through time. Gilmore’s transcendence

seems to be regarded as genuine, even though Houdini’s is revealed to be a

trick. The editorial two-step between the two time periods seems to suggest that

on some level, Gilmore managed to bring to fruition Houdini’s unfulfilled

desires to move past the physical, or at least managed to come to terms with it.

When the camera finally settles down again, the year is

1893, and the setting is in an ornate hall after Houdini’s performance of his

escape act, “Metamorphosis”. As he cleans up his props after his audience

has left (an act of pure physicality by one supposedly above it), he’s

approached by Baby Fay La Foe, who asks him if he wouldn’t rather transcend

mere physicality. He protests, claiming that he becomes part of his cage during

his act, but she apparently sees through his lies and calls him a drone. Wearing

a gown that accentuates her impossibly slim waistline, she claims to be the

queen of drones, and suggests they couple. When she takes his hand, a stack of

collapsible chairs (which recall the yet to be seen metal plates that are

arranged at the top of the Chrysler building near the end of Cremaster

3) topples and her dog runs away, giving an ominous aura to their pairing.

Considering her implied assistance in the conception of Gilmore at the start of

the film, it seems that Barney sees Baby Fay, the female, as the orchestrator of

male potential, again addressing the series’ biological concerns. With the

circle completed, and the myth of Gilmore fully told, the camera goes back to

showing shots of the environment, ending in a black cave, where once again the

saddle from the start of the film appears. This leaves the viewer with a

circular narrative that places, like each of the Cremaster

films do, a cycle within the series’ overriding genetic cycle.

When the camera finally settles down again, the year is

1893, and the setting is in an ornate hall after Houdini’s performance of his

escape act, “Metamorphosis”. As he cleans up his props after his audience

has left (an act of pure physicality by one supposedly above it), he’s

approached by Baby Fay La Foe, who asks him if he wouldn’t rather transcend

mere physicality. He protests, claiming that he becomes part of his cage during

his act, but she apparently sees through his lies and calls him a drone. Wearing

a gown that accentuates her impossibly slim waistline, she claims to be the

queen of drones, and suggests they couple. When she takes his hand, a stack of

collapsible chairs (which recall the yet to be seen metal plates that are

arranged at the top of the Chrysler building near the end of Cremaster

3) topples and her dog runs away, giving an ominous aura to their pairing.

Considering her implied assistance in the conception of Gilmore at the start of

the film, it seems that Barney sees Baby Fay, the female, as the orchestrator of

male potential, again addressing the series’ biological concerns. With the

circle completed, and the myth of Gilmore fully told, the camera goes back to

showing shots of the environment, ending in a black cave, where once again the

saddle from the start of the film appears. This leaves the viewer with a

circular narrative that places, like each of the Cremaster

films do, a cycle within the series’ overriding genetic cycle.

* * * *

04-10-03

Jeremy Heilman