Cremaster 1 (Matthew Barney, 1995)

To thematically, if not chronologically, kick off his

five-film Cremaster cycle, sculptor/filmmaker Matthew Barney made Cremaster

1, a forty-odd minute long look in, above, under, and around a complex

visual metaphor. It’s the start of the series that, among other things,

metaphorically chronicles the biological process from the sexually

undifferentiated state that exists at conception to the full realization of the

sexual identity, which occurs with the maturation of the gonads. Because this is

the first entry in that cycle, representing the time that exists between

conception and the determination of sexual identity, it begins in an idyllic

state. It is the only segment of the series that does not feature Barney in any

of the roles, instead attempting to convey the state of gender neutrality by

featuring a cast composed entirely of similar looking, platinum blonde women.

They seem to represent the chromosomal pool of X chromosomes before the entry of

a Y, and the definition of maleness, became a possibility.

To thematically, if not chronologically, kick off his

five-film Cremaster cycle, sculptor/filmmaker Matthew Barney made Cremaster

1, a forty-odd minute long look in, above, under, and around a complex

visual metaphor. It’s the start of the series that, among other things,

metaphorically chronicles the biological process from the sexually

undifferentiated state that exists at conception to the full realization of the

sexual identity, which occurs with the maturation of the gonads. Because this is

the first entry in that cycle, representing the time that exists between

conception and the determination of sexual identity, it begins in an idyllic

state. It is the only segment of the series that does not feature Barney in any

of the roles, instead attempting to convey the state of gender neutrality by

featuring a cast composed entirely of similar looking, platinum blonde women.

They seem to represent the chromosomal pool of X chromosomes before the entry of

a Y, and the definition of maleness, became a possibility.

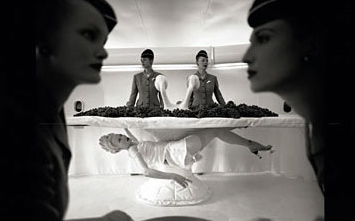

Set on and above a football field where a gaggle of women

perform elaborate, Busby Berkeley-style dancing routines, seemingly at the whim

of a controlling figure who floats in a pair of blimps above, Cremaster

1 acts as an introduction to the heavily coded symbolism that Barney

employs. The environment is a macrocosmic system that represents the first

stirrings of an organism’s development. The blimps, each emblazoned with

the Goodyear logo, represent the gonads (not yet either male or female at this

time, they could become either testicles or ovaries). The girls on the field

below seem to stand in for the chromosomes, their dance an organizing cellular

process. Within each blimp, there are similar contents: a table laid out with

grapes (red grapes in one blimp, green in the other), a sculpture that resembles

the gonadal structure (either of female ovaries and fallopian tubes or the male

testes and vas deferens), several nearly identical flight attendants, and, most

significantly, a woman under each table who seems increasingly in control of the

process.

It’s the development of this woman under the tables,

referred to in the credits as Goodyear, which gives Cremaster 1 what little narrative it has. Starting from a reluctant

fetal position, she unfurls within the perfectly white, cloistered womb that

exists under the tablecloth and begins using the handholds and footholds on the

underside of the table in the first representation of ascension in the series.

Using her hairpins, she burrows through the table above her and begins to pilfer

the grapes on the tables, which then pass through her foot to the floor below.

As this occurs, Barney cuts to the view of the football field below, showing the

anonymous dancing girls as they begin moving in symmetrical formations that are

initially obscure, but are revealed to correspond to the layouts of the grapes

on the floor of the blimp. Unlike the passive flight attendants who observer

their environment without much constructive interaction, Goodyear, who seems to

be a surrogate for the artist, begins to figure out the workings of the world

around her.

It’s the development of this woman under the tables,

referred to in the credits as Goodyear, which gives Cremaster 1 what little narrative it has. Starting from a reluctant

fetal position, she unfurls within the perfectly white, cloistered womb that

exists under the tablecloth and begins using the handholds and footholds on the

underside of the table in the first representation of ascension in the series.

Using her hairpins, she burrows through the table above her and begins to pilfer

the grapes on the tables, which then pass through her foot to the floor below.

As this occurs, Barney cuts to the view of the football field below, showing the

anonymous dancing girls as they begin moving in symmetrical formations that are

initially obscure, but are revealed to correspond to the layouts of the grapes

on the floor of the blimp. Unlike the passive flight attendants who observer

their environment without much constructive interaction, Goodyear, who seems to

be a surrogate for the artist, begins to figure out the workings of the world

around her.

Initially, the grapes fall to arrange themselves, but then

Goodyear observes and begins to control them, and the dancers below. Her

manipulations of grapes start out accidental, but they grow more intentional as

she gains confidence in her surroundings. When she reaches out to rotate the

sculpture, in a gesture of sexual definition, she gets a gob of white goo on her

hand, which she immediately incorporates into her “sculpture” by dabbing it

onto the tops of the grapes. This gesture shows how the artist’s experience

informs the work they created, but also seems to comment on Barney’s own work,

in which he sculpts using unlikely materials like Vaseline and tapioca. Since

the dabs of goo correspond with the Guggenheim-shaped hats that the dancers

below have been wearing all along, though, there seems to be the suggestion of a

two-way relationship between art and the world that it comments upon. It’s

also probably important to note that Goodyear doesn’t ever eat the grapes

(unlike one of the stewardesses, who does so covertly) when examining the way

that she seems to possess here a unique vision of the possibilities that exist

in her world. Her work with the grapes, and by proxy the dancers, culminates

with a visual representation of meiosis, the cellular process that occurs when

one germ cell forms four sex cells. This arrival at a sexual identity, gained

through her self-expression, gives her freedom.

Cremaster 1 is

perhaps the simplest of the Cremaster cycle,

but it has a coherency of vision that makes it hypnotizing. The vacuum of the

soundtrack creates a lulling atmosphere that drives home the impression that

this state is supposed to represent the most tranquil stage of development. The

emergence of xylophone music that tinkles above in the blimp is revealed to be a

formative version of the orchestral tune that the dancers parade to, further

stressing the theme of development. Barney’s approach gives a concrete

impression of the environment, conveying both its sense of scale and its spatial

relations. For one or two moments around the film’s 25-minute mark, the

movie’s brief runtime felt a bit excessive to me, since it seemed the same

points were being made repeatedly, but that notion passed as soon as it began

extending its themes again. The film’s compelling vision of the pre-sexual

phase of biological birth, like the stage in the creation of art before medium

or subject has been decided, shows the audience a moment of pure potential.

Cremaster 1 is

perhaps the simplest of the Cremaster cycle,

but it has a coherency of vision that makes it hypnotizing. The vacuum of the

soundtrack creates a lulling atmosphere that drives home the impression that

this state is supposed to represent the most tranquil stage of development. The

emergence of xylophone music that tinkles above in the blimp is revealed to be a

formative version of the orchestral tune that the dancers parade to, further

stressing the theme of development. Barney’s approach gives a concrete

impression of the environment, conveying both its sense of scale and its spatial

relations. For one or two moments around the film’s 25-minute mark, the

movie’s brief runtime felt a bit excessive to me, since it seemed the same

points were being made repeatedly, but that notion passed as soon as it began

extending its themes again. The film’s compelling vision of the pre-sexual

phase of biological birth, like the stage in the creation of art before medium

or subject has been decided, shows the audience a moment of pure potential.

* * * *

04-07-03

Jeremy Heilman