The Prefab People (Bela Tarr, 1982)

Bela Tarr’s early films examine the melancholy state of

the average Hungarian citizen’s life during the late 1970s and early 1980s

without much in the way of cinematic embellishment. The

Prefab People, which is the director’s third film, and the first of his

films to use professional actors, is the best of his early works because it

achieves such a degree of intimacy that its lack of ostentatious filmmaking

never impedes its ability to observe its characters. Essentially a two-character

piece that observes the turbulent relationship between a husband and wife, the

film, shot rapidly in ten days (with boom mikes casting shadows onto the action

from time to time), provides ample opportunities for the performers to showcase

their talents. The frantic opening scene starts as a husband begins packing his

things and calmly announces to his hysterical wife his intention to leave her.

Taking off from this point, the central topic of the film is their

disconnectedness from one another, and the claustrophobic living conditions that

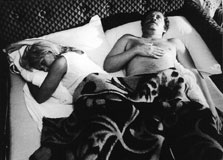

they share only makes that emotional state more ironic. They share a bed, but

rarely speak to one another about their feelings, which results in a

commonplace, but still acutely presented dysfunction. To his credit, Tarr never

makes their shopworn story out to be more than it is, even as he injects

political satire such as the husband’s befuddled and amusing attempt to

explain the differences capitalism, communism, and socialism to his son.

Bela Tarr’s early films examine the melancholy state of

the average Hungarian citizen’s life during the late 1970s and early 1980s

without much in the way of cinematic embellishment. The

Prefab People, which is the director’s third film, and the first of his

films to use professional actors, is the best of his early works because it

achieves such a degree of intimacy that its lack of ostentatious filmmaking

never impedes its ability to observe its characters. Essentially a two-character

piece that observes the turbulent relationship between a husband and wife, the

film, shot rapidly in ten days (with boom mikes casting shadows onto the action

from time to time), provides ample opportunities for the performers to showcase

their talents. The frantic opening scene starts as a husband begins packing his

things and calmly announces to his hysterical wife his intention to leave her.

Taking off from this point, the central topic of the film is their

disconnectedness from one another, and the claustrophobic living conditions that

they share only makes that emotional state more ironic. They share a bed, but

rarely speak to one another about their feelings, which results in a

commonplace, but still acutely presented dysfunction. To his credit, Tarr never

makes their shopworn story out to be more than it is, even as he injects

political satire such as the husband’s befuddled and amusing attempt to

explain the differences capitalism, communism, and socialism to his son.

The wife’s grievances seem at first to be entirely

justified, thanks to Tarr’s decision to start with the scene showing the

husband’s departure, but as the film proceeds and the audience is given a

chance to observe each of the characters as they interact with others and

contradict their previous statements, sympathies slide back and forth. For

example, after their modest ninth wedding anniversary celebration turns into an

opportunity for the wife to complain about her husband’s domestic sloth, he

makes their bed, without receiving or even expecting credit, while she cries

about his laziness. Her shortsighted need for instant gratification is a

constant thorn in her husband’s side because it sabotages any chance that he

has to advance in his career and give his family a better life. She responds

with envy and curiosity when he friends at the beauty parlor describe their

elaborate vacations, but when her husband is offered a better-paying job that

would temporarily take him out of the country, she protests his intended

acceptance, using the needs of the family as an excuse to shield her own

insecurities (and ironically putting herself in a position where she’s liable

to lose him permanently). Because of an earlier scene that shows the husband’s

obvious jealousy when a single friend is able to accept a lower paying job that

only requires him to work one day per week, the audience is aware of the

unspoken tensions that exist between the couple.

The wife’s grievances seem at first to be entirely

justified, thanks to Tarr’s decision to start with the scene showing the

husband’s departure, but as the film proceeds and the audience is given a

chance to observe each of the characters as they interact with others and

contradict their previous statements, sympathies slide back and forth. For

example, after their modest ninth wedding anniversary celebration turns into an

opportunity for the wife to complain about her husband’s domestic sloth, he

makes their bed, without receiving or even expecting credit, while she cries

about his laziness. Her shortsighted need for instant gratification is a

constant thorn in her husband’s side because it sabotages any chance that he

has to advance in his career and give his family a better life. She responds

with envy and curiosity when he friends at the beauty parlor describe their

elaborate vacations, but when her husband is offered a better-paying job that

would temporarily take him out of the country, she protests his intended

acceptance, using the needs of the family as an excuse to shield her own

insecurities (and ironically putting herself in a position where she’s liable

to lose him permanently). Because of an earlier scene that shows the husband’s

obvious jealousy when a single friend is able to accept a lower paying job that

only requires him to work one day per week, the audience is aware of the

unspoken tensions that exist between the couple.

Looser and a bit less portentous than Tarr’s other early

work, The Prefab People is so

unpretentious and specific in its characterizations that I imagine its

characters will likely feel less like Eastern Europeans from twenty years ago

than people familiar to the viewer. It also contains, what I believe is Tarr’s

first truly great shot. At the end of a night of drinking and disappointment,

the husband and wife sit at a bar with a crusty Mariachi singer as she waits for

him to get enough of his good cheer out of his system so they might leave. The

camera pans back and forth to a close-up of each of their faces as they continue

on, unwilling to inch toward each other’s mood, so that they might enjoy

themselves together. It’s an unshakable moment that reveals as much as any

dialogue scene between the pair. The

Prefab People’s final sequence features a shopping trip in which the

husband and wife, still together after their latest flare up, go on a shopping

trip to purchase a washing machine. The unsubtle message here that their

relationship runs in repeating cycles seems a fitting resolution to this

particular story. Any major catharsis would probably feel like a cheat because

definitive solutions to these characters’ problems seem beyond their grasp.

The movie’s almost random rhythms are set up so that each episode in their

lives seems to offer the promise of something new, but ultimately presents

nothing that hasn’t been presented before. Guessing whether their

non-communicativeness causes their frequent, violent explosions at each other or

vice versa is an exercise in “Chicken or egg?” futility.

Looser and a bit less portentous than Tarr’s other early

work, The Prefab People is so

unpretentious and specific in its characterizations that I imagine its

characters will likely feel less like Eastern Europeans from twenty years ago

than people familiar to the viewer. It also contains, what I believe is Tarr’s

first truly great shot. At the end of a night of drinking and disappointment,

the husband and wife sit at a bar with a crusty Mariachi singer as she waits for

him to get enough of his good cheer out of his system so they might leave. The

camera pans back and forth to a close-up of each of their faces as they continue

on, unwilling to inch toward each other’s mood, so that they might enjoy

themselves together. It’s an unshakable moment that reveals as much as any

dialogue scene between the pair. The

Prefab People’s final sequence features a shopping trip in which the

husband and wife, still together after their latest flare up, go on a shopping

trip to purchase a washing machine. The unsubtle message here that their

relationship runs in repeating cycles seems a fitting resolution to this

particular story. Any major catharsis would probably feel like a cheat because

definitive solutions to these characters’ problems seem beyond their grasp.

The movie’s almost random rhythms are set up so that each episode in their

lives seems to offer the promise of something new, but ultimately presents

nothing that hasn’t been presented before. Guessing whether their

non-communicativeness causes their frequent, violent explosions at each other or

vice versa is an exercise in “Chicken or egg?” futility.

* * * 1/2

02-28-03

Jeremy Heilman