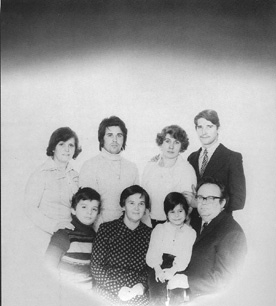

Family Nest (Bela Tarr, 1977)

Family

Nest, director Bela Tarrís realistic first feature (astonishingly made

when the director was 22) about the 1970s Hungarian housing crisis opens with

the quote: ďThis is a true story. It didnít happen to people in the film,

but it could have.Ē Considering the proliferation of non-professional actors

in this movie, that statement probably isnít too far from the truth. In a

departure from the intensely stylized, heavily choreographed camerawork that

dominated his later masterpieces made after Damnation,

he shoots Family Nest in a verite

style with direct, environmental sound, location shooting, and editing thatís

a bit too rough to be artful. As such, itís a film thatís way more

conventional than Tarrís later works, and not nearly as visually satisfying.

The outlook of life here is so unrelentingly bleak that at one point when Tarr

inserts a carefree montage at a local carnival that plays out with the

accompaniment of pop music feels wholly out of place until Tarr concludes the

sequence with a close-up of a character vomiting, a shock stunt that puts thing

back on track. As in nearly all of Tarrís films, the dingy barroom is only

escape from dingy houses that the characters live in, and alcoholism seems the

inevitable reprieve from their miserable lives.

Family

Nest, director Bela Tarrís realistic first feature (astonishingly made

when the director was 22) about the 1970s Hungarian housing crisis opens with

the quote: ďThis is a true story. It didnít happen to people in the film,

but it could have.Ē Considering the proliferation of non-professional actors

in this movie, that statement probably isnít too far from the truth. In a

departure from the intensely stylized, heavily choreographed camerawork that

dominated his later masterpieces made after Damnation,

he shoots Family Nest in a verite

style with direct, environmental sound, location shooting, and editing thatís

a bit too rough to be artful. As such, itís a film thatís way more

conventional than Tarrís later works, and not nearly as visually satisfying.

The outlook of life here is so unrelentingly bleak that at one point when Tarr

inserts a carefree montage at a local carnival that plays out with the

accompaniment of pop music feels wholly out of place until Tarr concludes the

sequence with a close-up of a character vomiting, a shock stunt that puts thing

back on track. As in nearly all of Tarrís films, the dingy barroom is only

escape from dingy houses that the characters live in, and alcoholism seems the

inevitable reprieve from their miserable lives.

The political mess that is

Hungary during the Ď70s is represented in the microcosmic situation that the

extended family at the center of the film faces. The external struggles of

communism are combined with a home life filled with overbearing fascism, borne

out of frustration with the ramshackle, tight-knit living conditions. Ceaseless

political messages stream off the television courtesy of government sponsored

news programs, and the din is worsened by the thin walls and close quarters of

the apartment which makes it impossible to shut out. The examined family

contains a mother, a father, two twentysomething sons, a daughter-in-law, and

her daughter, and the film opens with the return of one of the sons from his

extended stint in the military. Due to financial strain and governmental red

tape in the housing dispersion process, all of the family lives under one very

small roof. Itís a desperate and explosive situation in which nerves are shot

and tensions frequently rise among the family members, and it becomes incredibly

shocking to find out that the young coupleís two years of waiting for a flat

of their own have only gotten them in a position where they need to wait two

more years for one.

The political mess that is

Hungary during the Ď70s is represented in the microcosmic situation that the

extended family at the center of the film faces. The external struggles of

communism are combined with a home life filled with overbearing fascism, borne

out of frustration with the ramshackle, tight-knit living conditions. Ceaseless

political messages stream off the television courtesy of government sponsored

news programs, and the din is worsened by the thin walls and close quarters of

the apartment which makes it impossible to shut out. The examined family

contains a mother, a father, two twentysomething sons, a daughter-in-law, and

her daughter, and the film opens with the return of one of the sons from his

extended stint in the military. Due to financial strain and governmental red

tape in the housing dispersion process, all of the family lives under one very

small roof. Itís a desperate and explosive situation in which nerves are shot

and tensions frequently rise among the family members, and it becomes incredibly

shocking to find out that the young coupleís two years of waiting for a flat

of their own have only gotten them in a position where they need to wait two

more years for one.

They realize the futility of

their struggle against beauracracy, but have nothing to do but struggle against

it, and in Tarrís committed portrayal of their pathetic fight, his

political rage becomes acutely felt. One gets the impression that Tarr is

clearly outraged by the entire system and hopes that his film will cause enough

rage in the viewer to upset it. Still, the filmís dialectical process is far

too simple for its own good and disarms much of its hard won realism. After Tarr

shows scenes in which the familyís overbearing patriarch reprimands his

offspring for patronizing the local bar and committing adultery, he cuts to a

scene where he shows the father engaging in these same activities. Despite any

moralistic weaknesses, however, the audience is made acutely aware of the

strains placed on those in this situation. The daughter-in-law, desperate to

leave, has an astonishingly acted scene at the housing office that has her

begging, being abrasive to, and appealing to the reason of the employee who

controls her apartments applicationís fate, all to no avail. The series of

compromises presented here results in a broken system that practically asks

people to squat in living spaces that the government hasnít yet gotten around

to assigning because the red tape required to get a home legally is so tangled.

The final non-narrative interviews of the husband and wife, conducted

separately, are heartbreaking, first and foremost because they show them

confessing their disappointment and breaking down in tears for the first time

separately, and not as a couple. Itís horrible to realize that after being

together for seven years, theyíve moved toward none of their goals as a couple

because of the pressure of the system, and as both clearly state that they

believe a flat of their own would allow their relationship to begin improving,

the dire situationís impossibility only becomes more pronounced.

They realize the futility of

their struggle against beauracracy, but have nothing to do but struggle against

it, and in Tarrís committed portrayal of their pathetic fight, his

political rage becomes acutely felt. One gets the impression that Tarr is

clearly outraged by the entire system and hopes that his film will cause enough

rage in the viewer to upset it. Still, the filmís dialectical process is far

too simple for its own good and disarms much of its hard won realism. After Tarr

shows scenes in which the familyís overbearing patriarch reprimands his

offspring for patronizing the local bar and committing adultery, he cuts to a

scene where he shows the father engaging in these same activities. Despite any

moralistic weaknesses, however, the audience is made acutely aware of the

strains placed on those in this situation. The daughter-in-law, desperate to

leave, has an astonishingly acted scene at the housing office that has her

begging, being abrasive to, and appealing to the reason of the employee who

controls her apartments applicationís fate, all to no avail. The series of

compromises presented here results in a broken system that practically asks

people to squat in living spaces that the government hasnít yet gotten around

to assigning because the red tape required to get a home legally is so tangled.

The final non-narrative interviews of the husband and wife, conducted

separately, are heartbreaking, first and foremost because they show them

confessing their disappointment and breaking down in tears for the first time

separately, and not as a couple. Itís horrible to realize that after being

together for seven years, theyíve moved toward none of their goals as a couple

because of the pressure of the system, and as both clearly state that they

believe a flat of their own would allow their relationship to begin improving,

the dire situationís impossibility only becomes more pronounced.

* * *

02-21-03

Jeremy Heilman